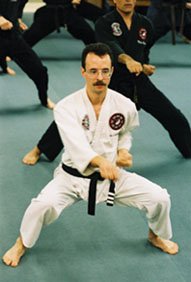

Blankenship Martial Arts

Martial Art As Science  Martial Art As Philosophy

Martial Art As Philosophy

Our system is eclectic in that it is composed of multiple styles of martial arts and diverse skills. It is not eclectic in the normal use of the word in the martial arts industry, which generally refers to a “best elements” homogenization of styles, as interpreted and organized by some individual or group who desire to create a “new” system of training.

Our system is eclectic in that it is composed of multiple styles of martial arts and diverse skills. It is not eclectic in the normal use of the word in the martial arts industry, which generally refers to a “best elements” homogenization of styles, as interpreted and organized by some individual or group who desire to create a “new” system of training.

In our school, the two formal, integrating curricula are each comprehensive systematized presentations of multiple complete systems of training, which offer the student the ability to experience and assimilate all possible martial concepts within a dynamic structure.

Through forty-five years of rigorous research and compilation , this unique system has logically blended fifteen hundred years of martial arts history and training with cutting-edge cognitive and motor learning theory. The excellence and elegance of the repertoire of skills taught reflects the dedication and the singular achievements of each master in the lineage of our styles. We shall try to honor their past efforts with our own dedication to the training and our commitment to all our students.

Curriculum Skills

Complete open hand and foot skills

Tae kwon do, Karate, Kung Fu, Okinawa Te

Close-quarter self-defense and grappling techniques

Judo, Jiujitsu, Hapkido, Aikido

Internal martial styles

Tai Chi, Chi Kung

Weapons training

Long staff, short staff, broadsword, knife, rope, chain, tiger fork, monkey staff, and others

Meditation

Concentration, meditation, and contemplation exercises for self-development, self-direction, and self-control of the mind

Breathing

Twelve different breathing methods are learned between beginning and advanced levels of skill. These breathing techniques are the essential integrating functions linking the physical/physiological changes with the mental development.

Supplementary

Although not a part of the general curricula, students may request assistance through the training with health issues, diet, cross-training and sport-related goals, supplementary resistance exercise programs, stress alleviation, repatterning, and a variety of other possible interests the student may wish to address through the system.

Curriculum Benefits

- Both aerobic (cardiovascular/cardiopulmonary) and anaerobic (power/strength) conditioning

- Increase in power, strength, endurance, and flexibility

- Improved balance, agility, grace, and coordination

- Bodyweight normalization (either weight loss or gain as appropriate)

- Self-discipline and self-control

- Stress-reduction and stress-management

- Optimized physical and mental development

- Integration of mind and body

- Physiologically correct and safe stretching techniques

Seminars

Several seminar series and specialty classes are offered, including but not limited to:

- Five-part pragmatic self-defense series

- Breathing and meditation seminars

- Specialty weapons classes (sword; spear; chain; monkey staff; short, intermediate and long hardwood staff; tiger fork; plum blossom knife)

- Vital points

- Sport-specific training methods

- Martial arts resuscitation techniques

- Sum-yi chi kung

- Semi-annual health promotion seminars

Age

We often receive calls from parents who, understanding how broadly beneficial good martial arts training can be for their children, are interested in determining whether a child is old enough to begin the training.

We often receive calls from parents who, understanding how broadly beneficial good martial arts training can be for their children, are interested in determining whether a child is old enough to begin the training.

We consider three variables when we determine whether to allow a child to enroll in our junior curriculum:

- Level of motor developmental skills

- Cognitive level

- Origin of interest and expectations of the student

Almost all children are ready to begin our curriculum by about six years of age; a significant percentage of five-year-olds are motorically and cognitively advanced enough; and, occasionally, a child of four can thrive in the classes.

Child Development

Since martial arts can be so important for a child's development, we strongly urge parents not to rush the child into an activity which, while fun in part, has an element of work and repetitiveness that the younger child might find too difficult. Play-type environments, masquerading as martial arts schools, may keep the child's attention, but fail to instill the most important elements for a child's complete development which a professionally designed and administered program would offer.

Although many schools treat martial arts predominantly as a game, sport, or fantasy activity, we teach children's martial arts as a:

- Foundation for physical/athletic skills of all types

- Tool for improving concentration and critical thinking skills for academic enhancement

- General practice for self-discipline, self-control, and self-esteem

- Model environment to learn respect for self and others

Direction

Of course the child should be having fun while learning, but the child should be directed to:

Of course the child should be having fun while learning, but the child should be directed to:

- Discover how to overcome the obstacles and challenges of life

- Become self-directed and self-motivated

- Develop self-confidence and courage

- Learn both cooperative social behaviors and leadership skills

- Gain awareness and control of his/her body

We try for an equal balance of sweat and smiles.

Please call (512) 452-3618 to schedule a visit for you and your child during one of our class observation periods.

A complete martial arts curriculum covers every aspect of mind/body development within the context of a repertoire of martial skills.

The purposes of the development of the body and mind through martial arts training are: to enhance health/fitness, longevity, and a variety of performance variables; to build a congruent lifestyle, with emphasis on self-discipline and goal-attainment, personal integrity, and respect for others; to develop a superior set of defensive and offensive skills and impeccable self-defense ethics; and to mold a personal understanding of how to use the core principles of such a discipline to live a happy and fulfilling life.

The teaching of the martial-specific aspects of the curriculum is designed to contribute directly to the mind/body infrastructure as well as to pragmatic self-defense abilities, but, being a martial art instead of sport or combat, the discipline is purposefully organized to teach the student how to generalize and apply the practice to every aspect of daily living.

Unless one intends to be a karate, kickboxing, or jiujitsu tournament fighter; is training for imminent combat; or is acutely involved in a very high-risk profession where the likelihood is high of frequent life-threatening circumstances; then true martial arts training should follow the traditions that have been passed on for the past many centuries. Only training in this systematic way can guarantee that the student will benefit in the optimal way from the practice.

Someone may learn a set of reasonable defense skills, but he may still be almost completely undeveloped as a whole person: capable of success in any endeavor; living a mentally sound and physically healthy lifestyle; being a responsible and integrated member of his communities and organizations; living his goals and dreams with boldness; having a positive, generous, and cooperative outlook; finding happiness and sharing it with others; viewing the stresses of life as challenge and opportunity. These are the abilities and attitudes of someone who has been trained correctly in martial arts.

In addition to the lack of overall-development characteristics of the "street-fight-mentality" type of training, that type of practice may also fail the practitioner in more salient self-defense functions. Most of the "reality" kinds of training deal only with the peripheral techniques of combat - they usually cover some level of physical conditioning; a set of strikes, blocks, kicks; a system of close-quarter, grappling skills; and a practice which builds some degree of fighting spirit.

Those are all valuable and necessary components of self-defense capability. Yet, if character and spirit, awareness, fearlessness, commitment, self-control, and a continuum of ethical response options - from avoidance, verbal de-escalation, redirection, and control skills to ballistic attacking, submissions techniques, and nerve center resolutions- are not developed in concert with this approach, then the student may never understand that the true purpose of self-defense training is to learn how to never be attacked or, more appropriately stated, to have a process that continually tries to reduce the probability of attack to zero. The other defense-oriented purpose of right training is, of course, to give the martial artist the most highly effective physical skills.

In other words, by correctly learning and responsibly assimilating a personal arsenal of powerful and superior fighting techniques in a curriculum that stresses the development of mind and character equally with its concentration on technical skills, a true martial artist ultimately learns how to not fight. Although the martial artist should be prepared at any moment to commit clearly and completely to the battle, his correct training produces a peaceful nature and a respect for life. These are the superior results that have been produced by traditional training through hundreds of years of development, irrespective of the fact that they were produced through trial-and-error protocols.

If we can be sure to retain the functions that yield such superior mental development, our modern training methods, benefiting from exercise and cognitive sciences, are superior in many ways to these trial-and-error protocols, which have kept training dangerous and inefficient for many generations. Therefore, optimal martial arts training should be viewed as both traditional, in its foundation principles of perseverance, diligence, courage, integrity, humility, and loyalty; and dynamic, as it continues to evolve more effective techniques and training strategies through application of scientific principles of human learning and performance.

If a discipline can be accurately labeled a martial art - distinguishing itself from a simple fighting system, or a martially-influenced health and fitness regimen, or a karma yoga path of self-culture - it must have a systematized style of teaching to present continuous mental and physical challenge and growth - building a clear mind, powerful and healthy body, and an indomitable spirit. It must be a tool for daily use and for continuous improvement.

If we do not train primarily to develop foundation principles of higher mental development, wisdom, and understanding, but only train for fighting skill or physical development, then our expertise will be based predominantly on attributes like strength, speed, and endurance, or on tactics and tricks.

Strength, speed, and endurance can always be exceeded by someone larger or better-conditioned, and those parameters will also decline as we age. Tactics and tricks - sets of skills or tools applied in a martial context - vary in effectiveness based on individual differences in practitioners and in situational circumstances. Therefore training should optimize physical and tactical variables by using the movement set to teach core principles of movement dynamics and strategy.

The foundation principles of human movement are constant. The logic of tactical practice is simple and well known to all true masters of martial art. The principle concepts of open hand and foot skills, close-quarter grappling skills, and use of weapon classes have been understood, systematized, and transmitted for many generations.

The salient distinction between schools teaching martial skills has to do first with the depth to which the training penetrates the individual's awareness and precipitates profound change; and second, given that a master instructor truly understands, models, and communicates the foundation principles, the efficiency with which the student acquires a deep assimilation and use of the techniques. To impact in these ways, it is implicitly important that the foundation of the curriculum has a perfect correlation with the foundation of all types of learning and all types of inner growth.

Every lesson, regardless how diverse the topics seem to the beginner or casual student of martial arts, should present the conceptual core of training to the student. Every technique should contain the whole of martial arts theory, just as every strand of DNA holds the code for the whole individual. It is up to the individual, equipped through the training with the tools to achieve any goal, to discern a path on which to apply his understanding.

There is a great difference in a martial athlete or martial performer, and a martial artist. It also does not necessarily follow that a person capable of demonstrating a technique or skill can teach it effectively to someone else. So a course perceived and taught from a given peripheral bias, such as athletics or performance, will likely produce no greater result than that level of understanding. Such superficial levels of orientation soon become obvious, even to the beginning student. The selection of one's instructor becomes, therefore, the single most important variable in determining the potential achievement one may attain through the martial arts training.

As we come to know that our outcome - our rate and safety of progress; our potential for understanding the daily application of the class-work; our cultivation of health and fitness through the practice; our ability to protect ourselves and our families; and our honing of a tool for success in all endeavors - directly parallels the type of training we receive from the master instructor, we also come to know that our most important decision when we begin training in martial arts is to find a great teacher.

A final comment about teaching: we do not as much teach what we know as what we are.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What if I have an injury? Can I still learn martial arts?

- How physically demanding is the training?

- Is martial arts a religion? Will it conflict with my personal beliefs?

- Do I have to compete? Can I compete?

- How long does it take to get a black belt?

- What can I read? What websites should I visit?

- How long will it take me to be able to defend myself?

What if I have an injury? Can I still learn martial arts?

One must be realistic about one's physical condition when he or she considers entering a martial arts school. The practice regimens and technical requirements of some programs may be inappropriate for a given injury or type of physical idiosyncrasy.

A person with a torn anterior cruciate ligament should not do flying kicks; nor should a person with a severe rotator cuff tear engage in intense grappling. I mention those particular conditions and their restrictions on certain presentations of martial arts because I have had both injuries myself, and I am a fully functioning martial artist able to do everything I want and need to do to attain a superior level of skill and any other attribute I wish through the training.

I should also mention that the first injury was sustained in a basketball game, and the second was in a Frisbee football game; both have been rehabilitated through special rehabilitative sets that we teach here at the school. Now I practice intelligent and effective kicking techniques, and I also practice jiujitsu-style grappling twice a week.

If you have a pre-existing injury or a physical anomaly about which you have concern, a highly qualified instructor can assist in various ways. First, the instructor should have enough knowledge about such topics that he knows whether you need to consult with your doctor before you begin a martial arts training program.

However, the problem in consulting with most physicians is that they may have a preconceived notion about what "all" martial arts training entails, so they often will give opinions, albeit well-intended, from a position of relative ignorance. Their own experience or their inferences from media presentations of martial arts can influence them to either approve of a possibly dangerous training protocol or prohibit one which might prove very beneficial to the prospective student.

Therefore, it becomes of paramount importance, especially if the existing injury or physical anomaly could be significantly, either positively or negatively, affected by the training, for the physician, the instructor, and the student to discuss the expectations of the curriculum, its possible ramifications for the student, and the goals the student has in undertaking the training.

If the experience and knowledge of the instructor do not include a way for the student to protect and, hopefully, rehabilitate the injury in the context of attaining his goals in the curriculum; or to circumvent by individual design the impingement of the training on the injury or anomaly; then training in that environment increases the risk of injury or failure.

In our opinion, the training exists only to serve the student's goals, and as such, must be adaptable for the special needs and aspirations of the student. A rigid set of criteria for practice or advancement, which cannot help all people, indicates only that the instructor has not truly mastered the art himself and can, therefore, never be expected to be able to guide the student to mastery.

How physically demanding is the training?

There is no simple answer to this question since the goals and experiences of every person in the training hall are unique to themselves.

I think that it is important for anyone interested to avail themselves of all the possible benefits achievable in a good martial arts curriculum, and one of those benefits is most certainly an enhancement of fitness.

The archaic pictures painted in martial arts stories about the punishing and dangerous methods and regimens which damaged and scarred people's bodies and, supposedly, instilled superior fighting skills and indomitable spirit, harbor some of the greatest dangers and are some of the most misleading directives in martial arts lore.

Certainly training methods have been and continue to be concerned with establishing a level of physical rigor in the development of the individual. However, those schools, current or historical, which take pride in the badges of injury and physical discomfort worn and related by their students; and those students and teachers who subject themselves and their classmates to such a juvenile and outdated approach will do more, and possibly permanent, damage to their bodies and spirits than the negligible benefit they may accrue from such a sophomoric perspective.

Many of those people simply don't know any better, not having used an intelligent set of criteria in the first place for selecting a school. They are often just doing what they are told or what they saw someone else do, and they have no data with which to make a comparison. After a while, even if they are exposed to a track which achieves superior results safely, both in physical conditioning and defensive skills, their own cognitive dissonance may prevent a logical conclusion for them. It is important to train properly from the outset and to reduce or eliminate the probability of acute, traumatic and of chronic overuse injuries.

An intelligent approach to increasing physical rigor is assured by first assessing the initial physical condition of the student and then moving him appropriately through various levels of physical intensity over a long period of time.

In the earliest stages of training, it is important to listen to the alarm signals the body is giving us about what is an acceptable level of challenge, so the student must be actively involved in the ongoing assessment process and give the instructor accurate feedback about fatigue and, generally, about how the body feels during the training.

If the beginning student has not been involved recently or ever in regular exercise, or if the beginning student is a current professional athlete, the student is entering a new activity with new requirements for the body. The student and the instructor must work together and pay close attention to how the student's body is responding to the practice. Each student is unique and each student must be guided by the professional teacher to involve himself at a safe intensity and to build that intensity over weeks or months to the required level for the goals of the student.

Most of us are such goal-seeking animals that our tendency is to push too hard rather than to do too little, especially when we are in an environment where the mere presence of others motivates us to push beyond our normal bounds. It becomes the obligation of the staff to monitor and suggest when we should rest and recover so that we can make steady progress instead of self-inflicting nagging little strains or excessive soreness which detour us from our goals.

A superior martial arts training program will guarantee better and more comprehensive fitness and health adaptations than virtually any other discipline, but it can only exist if the instructors have the knowledge and the attitudes that assure it. Safe and enjoyable physical challenge is an essential part of the training experience, and will guarantee the health and fitness of the physical body as well as the continuing blossoming of impeccable martial spirit. The trials and challenges of the true path of the legendary martial arts masters has always been one of accessing the greatest heights of achievement through walking the steady path of development.

Is martial arts a religion? Will it conflict with my personal beliefs?

Although in the Orient martial arts has been practiced by Taoists and Buddhists and has become linked with those religions in the minds of some people, martial arts practice is completely independent of any direct connection to a given faith or set of religious beliefs.

One aspect that traditional martial arts shares with virtually all of the great faiths in the world is a creed of behavior which reveres life and peace; fosters harmonious interactions among people; acknowledges our connection to all things on the planet; and tries to instill in its practitioners a strength of character and a reservoir of will which will help the martial artist have courage and compassion as he walks through life.

One might assume, therefore, that an individual’s personal spiritual beliefs and aspirations, regardless of what you call them, will be fortified and embellished through the training.

Do I have to compete? Can I compete?

Our participation as a sport organization ended many years ago. We sent students to tournament-type competitions for the first few years our school existed, partially out of curiosity and partially because it was appropriate because of our membership in a national organization.

The students always performed exceedingly well, but the general conclusion we reached was that we wanted to concentrate our practice for two specific purposes, neither of which accommodated martial arts as a sport.

Our orientation is to teach martial arts as a tool for improving one’s life in whatever way the student can conceive to apply it, and we believe that martial art must be taught to create the most realistic and pragmatic self-defense system possible. While one could tune their practice in the sport environment to address these goals, we felt that it was somewhat inefficient for us to have the “distraction” and “game” of the tournament venue. We are a martial arts school – not a sport.

Therefore, our “competition” occurs within the structure of the class itself; with scores of instructors and hundreds of students training, our training environment rivals the competitive environment we might find outside the school, with the added benefit that you are always certain that your training partners will be impeccably concerned for your safety and that the competition is geared so that each person is helping the other person to push themselves to improve.

We are not immovably adamant that a student may not compete in sports events outside the school, but it will never be required, and it will be considered, determined, and effected on an individual basis.

The most important point we can make about competition, however, is that the true opponent -- the one who is most likely to confuse, distract, or defeat you and the one about which our training is clearly concentrated to master -- is yourself.

How long does it take to get a black belt?

Students progress at their individual pace. We realize that people have busy lives: work, school, relationships, hobbies, travel. We encourage our students to lead balanced and rich lives, maintaining their priorities and keeping all their commitments.

Therefore, people come to view their advancement differently. A given student may attend class very regularly for years and progress rapidly. Another may want or be required, because of lifestyle requirements, to adopt a schedule that is less rigorous; they will be content with advancement over a slightly longer time.

We consider the rank of black belt to indicate an expert-rated martial artist, and, since our system is very comprehensive and our requirements of technical excellence are high, one should expect to take from four to several years to advance to the level of first-degree black belt.

We frequently have guests visit the school who have been awarded, in a couple of years, a black belt or multiple black belts in other styles. Although they have a different level of technical expertise and often a different repertoire of skills from our own students, their black belt is valid in that it accurately represents the requirement of the curriculum in which they have trained. The term “black belt” varies from system to system and from school to school.

So the length of time it takes to get a black belt depends on how good a black belt you want to be, and it depends on what system is awarding the rank.

What can I read? What websites should I visit?

Most of our guests and students, and you, of course, since you are looking for information on this site, are academically oriented. It is very normal, as you pursue a new interest, to seek out as much information as possible on the subject.

For some period of time I read everything possible about martial arts, from all the newsstand periodicals to every text published. I thought that increasing the breadth of my knowledge of martial arts would make me better and give me the benefit of many perspectives.

As a beginner, I exposed myself to a variety of training methods and tactical approaches, read all the curious myths and legends of martial arts, and learned about the training paths of the great historical personages. All of this fed my curiosity and gave me doses of inspiration from time to time.

I found for myself, and I have observed it in thousands of my students, that while this approach is not necessarily detrimental, it is probably not the way to give yourself the “right” foundation for the training.

In my opinion, it would be better to simply immerse yourself in the training without creating expectations, competing ideas, or a collection of junk from which you will eventually have to sort out the few simple and elegant concepts and discard the baggage that you have taken on from the reading.

How long will it take me to be able to defend myself?

Many instructors will claim that a given system or style will enable you to defend yourself in some determinable length of time. In my opinion, whether an instructor claims that the ability is achievable in six weeks or six years, the instructor who makes such a claim is doing a great disservice to the student. The instructor may not even be intentionally misleading his students; he may truly believe the not provable claims he makes. In our opinion, however, any instructor who makes the unqualified claim that he can teach you to defend yourself in a specific length of time, regardless of how long that period, is being untruthful.

First, when you consider self-defense, you must decide what set of skills or attributes that you desire to acquire as your repertoire of self-defense functions. After forty-five years of teaching, we have observed that most people, instructors included, have a very limited definition of what type of training is actually necessary to prepare someone to be able to defend himself.

Skill set acquisition should be designed in stages so that a simple but effective set of physical techniques is acquired quickly and easily. Conditioning and other practice benefits must be pyramided intelligently so that more demanding and more complex skills can be added over time. Attitudinal and emotional adjustments need to be instilled in conformation with the ethics and other personal beliefs of the student. The student should acquire the ability to analyze situations quickly; to make good “use of environment” choices; and to generalize tactical information to specific circumstances. The instructor has the obligation to educate the student to comprehensively broaden the scope of the student’s definition of self-defense.

It is much more important, for example, that the student learn behaviors and functions which will greatly reduce the probability of being attacked than to concentrate exclusively on a repertoire of physical skills. The techniques contained in every martial art and self-defense system have some pragmatic benefit, but simply acquiring mechanical ability to execute movements has very little to do with one’s ultimate ability to protect himself.

One can also presume that some individuals, whose mindset and reactions need only the addition of “what to do” technically, may be highly qualified to defend themselves with very limited exposure to training. However, the vast majority of us need frequent rehearsal and practice to safely simulate the physical requirements and emotional intensity of an actual encounter, so that we are prepared and willing to meet the physical, mental, and emotional demands of a life-threatening situation in as effective a way as possible. We improve our abilities optimally with equal attention to all the variables that reduce the probability of attack and increase the probability that we will resolve it according to our personal definition of ideal outcome.

The process of learning and changing behaviors takes time. Our possible attackers are usually experienced (professional), unpredictable, and highly aggressive; they may have accomplices and weapons; and they are highly motivated to find the way to achieve their objectives. How long does it take to learn to defend against them? Our curriculum is designed to optimize progress in every aspect of the self-defense function; it will make you better prepared every day.